- History

- Featured

- Jon Mark Beilue

Jon Mark Beilue: Harsh lessons from history

History students see parallels from disasters to today’s pandemic

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

— William Faulkner

Dr. Bruce Brasington has about 15 total and complete disasters in his Senior Seminar history class — and he couldn’t be more pleased.

“So far, it’s the best I’ve had,” said Brasington, professor of history at West Texas A&M since 1990. “Actually, I’ve had very few times where this class over the years has not been a slam dunk of great work. I come out of this class just on fire.

“That’s not to disparage previous classes, but with this level of commitment, willingness to work hard and be self-critical, this is one of the best classes I’ve taught at WT.”

The class is a capstone course, part of a three-course sequence all upper-level history majors must complete. The course has evolved over the last 15 to 20 years to blend writing, research, building arguments and taking a particular position.

The historical subject: Major disasters in North America from 1870 to 1914, an approximately 45-year span covering the post-Civil War period to prior to World War I.

The students, Brasington said, are well trained in local history, but in spreading out geographically, and doing so during a time period where disasters were more frequent because of lack of safety procedures and technology, these tragedies are an effective teacher.

When topics were selected in January, there was no concern the United States would soon face its own health, economic and social disaster with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic that began gripping the country and much of the world in March.

“This sounds arrogant, but history better make you humble,” Brasington said. “When you realize what so many people have confronted, the study of history is a heavy dose of humility. We don’t stand over the dead – the dead drive us to our knees.

“Secondly, students started to learn about people that history forgot. We learn their stories, like the group photo of an adult soccer team one of our students in Canada showed. They were so full of life and nearly all died in a mining disaster. History can be the voice of the dead.

“And then, history is not a thing. I tell my students history is not a noun, it’s a verb. It requires action. We see history as names and dates, but it’s supposed to act on us. It means something. It forces us to think and act in our world today.”

Students researched mining disasters, paralyzing weather, locust plagues, fires, shipwrecks and droughts. Commonalities emerged, some of which could be related to today’s pandemic.

Kolby Karr is a 2005 graduate of Amarillo High. He spent about 10 years working in the oil fields before deciding to pursue his affinity for history and use that to one day teach and coach. He paints houses to afford to attend WT, where he expects to graduate in December 2021.

Kolby Karr is a 2005 graduate of Amarillo High. He spent about 10 years working in the oil fields before deciding to pursue his affinity for history and use that to one day teach and coach. He paints houses to afford to attend WT, where he expects to graduate in December 2021.

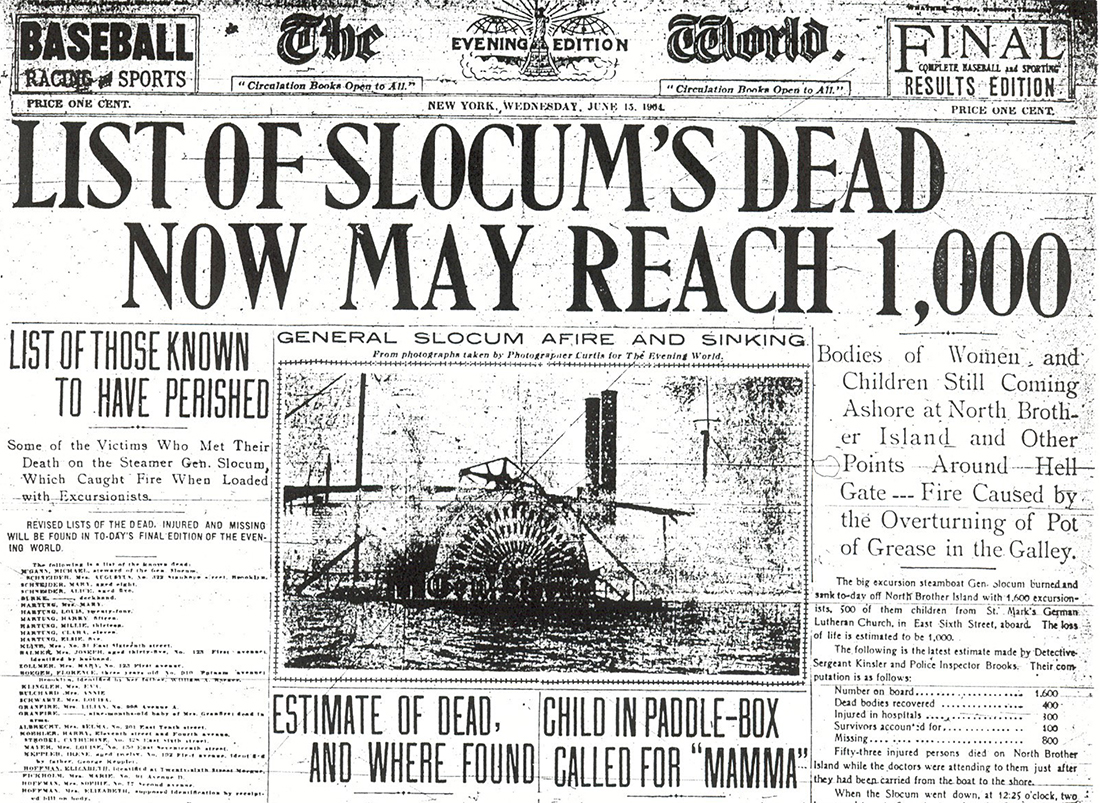

The General Slocum was a passenger steamboat in New York City. On June 15, 1904, it was supposed to ferry mostly women and children from the St. Mark’s Lutheran Church — German-Americans from Little Germany, Manhattan — across the East River to Brooklyn for a Wednesday afternoon picnic.

Not long after departing, fire erupted in the forward section. More than 1,000 out of 1,342 on board perished in the blaze. Husbands and fathers at work on that midweek afternoon lost entire families. It was New York’s worst loss of life until the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001.

“It was just fascinating to me,” Karr said. “What grabbed my attention was just the enormity, the amount of loss of life, and I had never heard of it.

“The blatant negligence and profiteering just jumped out at me,” Karr said.

There was no maintenance of safety equipment. Fire hoses were rotted. Lifeboats were few and inaccessible. Life preservers, out in the elements for 13 years, crumbled when put on. The crew had no training in fire safety.

“There was a laxity in the workplace culture especially in the New York harbor,” Karr said. “Things get overlooked until something terrible happens. That’s a fault with a lot of us. The higher-ups in that steamship company that owned the General Slocum were out to make money and willing to overlook things.”

Karr drew a parallel with today’s COVID pandemic and ongoing debates over how and when to reopen businesses.

“I look at (Division I) college football – games are being postponed, a number of players are getting sick, and there’s a sentiment that says we shouldn’t be putting people at risk this year,” Karr said. “Those most at risk are not getting paid. But there are a lot of TV dollars in play, and institutions have to make money. I understand what’s at stake, but you have to weigh the cost.”

WT, which has played a limited number of fall football games, does not profit from televised games as a Division II school.

Seven years after the General Slocum disaster, the Triangle Shirtwaist fire, also in New York, killed 145 immigrant women in what was a mostly preventable tragedy. A fire broke out in a scrap bin near the end of a work day on March 25, 1911 in the sweatshop on the ninth floor of the Asch building in New York.

The women, who worked 60 hours a week, died of smoke inhalation, jumped to their death, or were crushed. In an era where worker reform was becoming a growing issue, harsh conditions played a huge role in the disaster.

“Factory owners locked the doors to keep anyone from taking a bathroom break, and secondly, they didn’t want anyone to steal any fabric,” said Vee Mendoza, a junior from Fabens, in El Paso’s lower valley. “Fire escapes didn’t reach the ninth floor. Ladders from firefighters only reached the sixth floor. It was really devastating.”

“Factory owners locked the doors to keep anyone from taking a bathroom break, and secondly, they didn’t want anyone to steal any fabric,” said Vee Mendoza, a junior from Fabens, in El Paso’s lower valley. “Fire escapes didn’t reach the ninth floor. Ladders from firefighters only reached the sixth floor. It was really devastating.”

Garment unions were leading reform with strikes and protests. The Triangle Shirtwaist fire was a catalyst. There were some mild concessions to workers with a reduction of weekly hours to 54 and an increase in pay.

“The event was emblematic of what labor went through,” Mendoza said, “and what happened for there to be some kind of reform. It was a public outcry for change.”

Mendoza sees a parallel with today’s pandemic in appreciation of health care workers and teachers – careers that are often in the shadows. Essential workers who could not shelter-in-place have received admiration for soldiering on.

“COVID has disrupted many routines,” Mendoza said, “but we’ve stepped back and recognized those who’ve had to work in adverse situations. They are contributing to society more than we can imagine.”

Do you know of a student, faculty member, project, an alumnus or any other story idea for “WT: The Heart and Soul of the Texas Panhandle?” If so, email Jon Mark Beilue at jbeilue@wtamu.edu.