- History

- Jon Mark Beilue

The pandemic -- 100 years ago

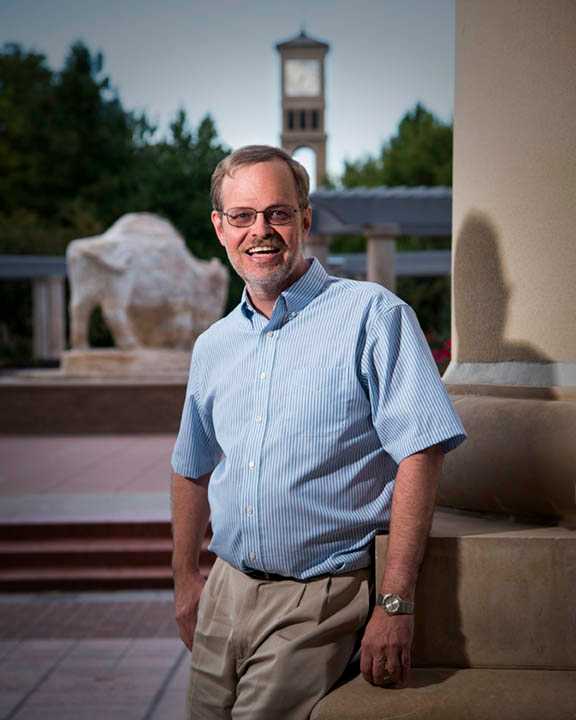

WT prof Kuhlman puts spotlight on local impact of Spanish Flu

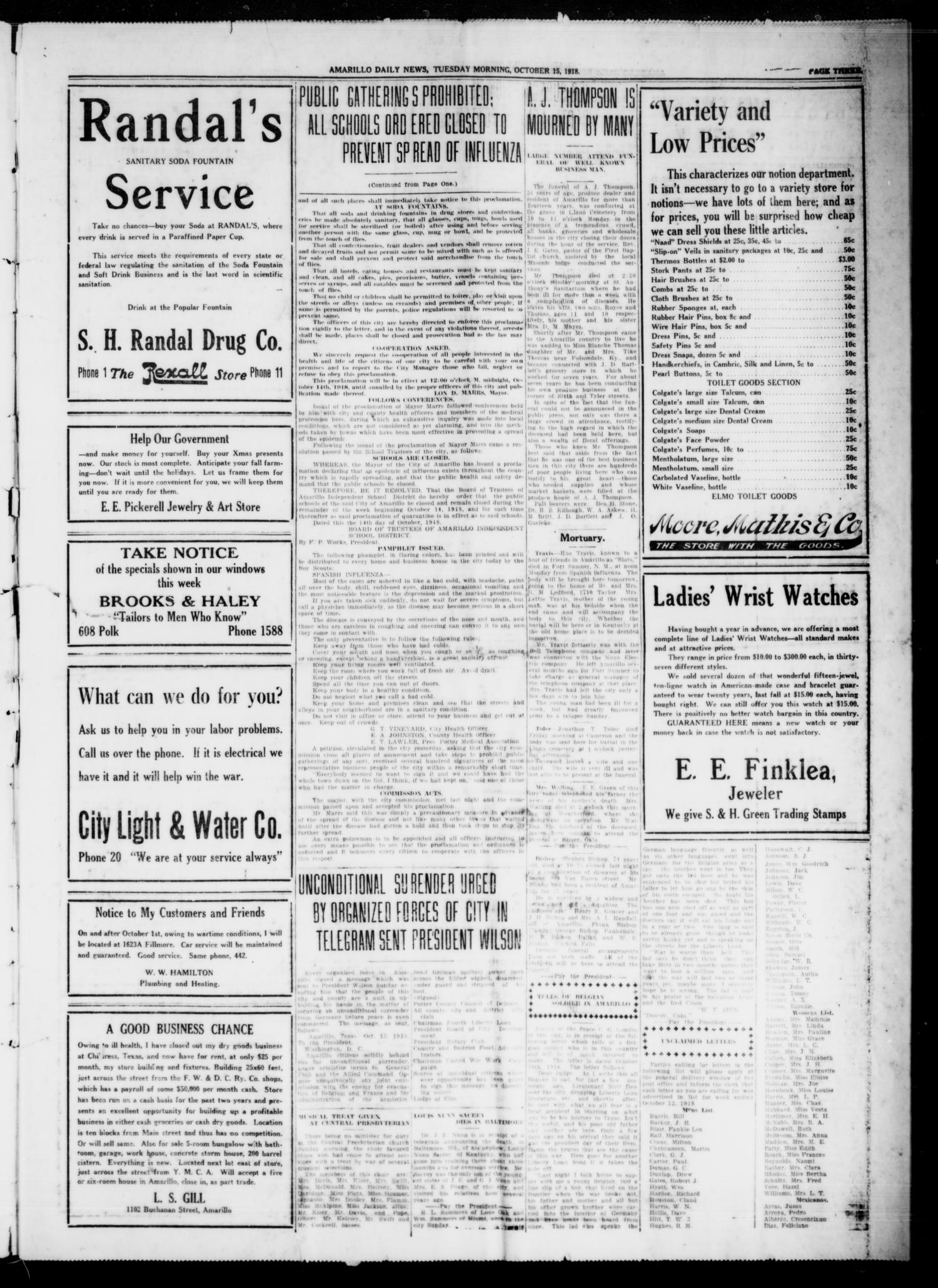

*Photo: A 1918 edition of the Amarillo Daily News issues a proclamation on the Spanish Flu.

Maybe in 25 to 50 years, history might treat the current COVID-19 pandemic in the same way history treated the last health pandemic of this kind – as more or less a forgotten footnote.

The Spanish flu pandemic just more than 100 years ago – in 1918-1919 – killed more than 12 times as many as the number of U.S. soldiers who died in the simultaneous World War I. In a global illness where as many as 50 million may have died, the flu claimed the lives of an estimated 7,000 Texans, and in the sparsely populated Texas Panhandle, as many as 75 succumbed to the virus.

But if not for the current pandemic that’s affected in some way almost every facet of life in the United States, the one that was much more debilitating a century ago, so far resulting in about six times as many deaths, would remain largely unknown.

“Today, it’s not even a blip in history,” said Dr. Marty Kuhlman, professor of history at West Texas A&M. “This one (COVID) might be like that too even though it’s changed our nation in a number of ways.

“It will be interesting to see if historically how much and how people will look back on the pandemic. In history classes today, there’s a lot taught about World War I when looking at the early part of the 20th century, but not much about the Spanish Flu, but this was much more deadly.”

At the urging of his father, Kuhlman, the editor of the Panhandle-Plains Historical Review, researched how the Texas Panhandle responded to the 1918 flu pandemic and what kind of impact it had locally. That research resulted in a pair of stories for the Caprock Chronicles, an online series of stories spotlighting history and the sites of West Texas.

There were no Zoom meetings 102 years ago. No #allinthistogether hashtags, no color-coded levels of alert, no press briefings. But there didn’t seem to be a political standoff on the wearing of masks – which was encouraged along with a slathering of Vick’s VapoRub – nor were there any record of organized protests of rights being infringed despite some pretty draconian measures put in place.

There was though some finger-pointing as to where both viruses originated. Today, there’s the occasional reference to the Chinese Virus and Wuhan Virus, usually a political point made to the origin of COVID-19.

“Spanish” flu, sometimes referred as “Spanish Lady,” came from what is incorrectly believed as its origin from the Iberian Peninsula. Many European countries blamed the other, but there’s no universal consensus about where it actually originated, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The first case in the U.S. was in March 1918 at Fort Riley in Kansas.

‘Serious danger confronts us’

The Spanish flu pandemic hit the Panhandle with force just a few weeks before the end of World War I and the fight against Germany. Amarillo city manager Jeff D. Bartlett tried to capitalize on the spirt of that day. Though not sure how this would restrict the flu, Bartlett, according to Khulman’s research, called upon “our army of citizens” to eradicate every weed in the city limits and clean up all premises.

Bartlett associated the fight against the influenza with the fight against Germany. He called the virus “Kaiser’s friend,” in reference to Kaiser Wilhelm II, emperor of Germany.

Amarillo took particular precautions against the Spanish Flu based on how other regions responded. In Philadelphia, the public health director allowed a Liberty Loan parade to go through city streets unchecked. The deadly virus soon spiked in the city.

In early October, concerned about what was occurring in the larger cities, Bartlett issued a warning in the Amarillo Daily News and through a circular distributed in public places that “a serious danger confronts us and prompt and effective measures must be taken.”

One day after the first reported case — John Woods of Kress — was quarantined, Amarillo city health officer Dr. E.T. Vineyard on Oct. 4 issued a “clean up and keep clean” order and authorized the police to “begin a rigid inspection of all places.” Those not in compliance would be reported.

It was about the middle of October that Amarillo mayor Lon D. Mars issued an order to close the majority of public places such as schools, churches, theaters, and many businesses. Violators were subject to arrest. Tattletales were encouraged.

Mars urged citizens “to report to the City Manager those who fail, neglect or refuse to obey this proclamation.” The Daily News reported widespread support of the order.

“I did find some protest,” Kuhlman said, “but not much. In Dallas, some of the business people were angry about closing that’s similar to today, but from what I’ve seen, the public seemed a little more receptive than today.”

Amarillo, with a population of approximately 15,000, continued to be aggressive in fighting the pandemic. The schools remained closed until mid-November, then closed again from Dec. 6 to Jan. 13. A proclamation in the Oct. 22, 1918, edition of the Daily News directed police to isolate and quarantine any persons with symptoms on the street or in a public place.

*Photo: "Today, it's not even a blip in history," said Dr. Marty Kuhlman who researched and wrote two stories for the Caprock Chronicle on the 1918-1919 Spanish Flu. The virus killed an estimated 675,000 in the United States.

Tulia, the young, hit hard

“I found it interesting how much authority was taken by local public officials,” Kuhlman said. “The mayor took on a lot. Not saying our mayor today is not doing that, but there doesn’t appear to be any higher authority, no direction from the governor like we see today.”

Kuhlman’s later research might confirm as a reason why. William Hobby, the Texas governor, had other things on his plate. He was fighting the Spanish flu and convalescing in Beaumont.

By Nov. 9, there were 33 deaths from the 1918 pandemic. Two days later was the end of World War I. Citizens ignored the advice to avoid large crowds. The city celebrated the end of the war, according to the Daily News, “as thousands packed the vacant lot opposite the post office and overflowed upon the pavement.” There was a spike in cases after that.

Of all Panhandle communities, Tulia was particularly hard hit. The town was about three weeks behind Amarillo in closing schools, which was believed to be a factor. There were more than 300 cases in Tulia, and the Hotel Tulia was turned into a temporary hospital.

“Teachers in Tulia were required to go to the home of their students to give them lessons with emphasis on reading and arithmetic,” Kuhlman said, “and the parents were supposed to take over after that.”

What, no online lessons?

Unlike COVID-19, where the elderly seem more vulnerable, the 1918 pandemic hit hard those under 40. Roy F. Mitchell joined the Student Army Training Camp at West Texas State Normal College that September. He died a few weeks later. Tildon Tickett, 16, was among the first to die on Oct. 23.

Young women – Josephine Cheyne, 21, and Vera Livingston, 23 — died. Solon Randall, 33, an Amarillo pharmacist, was the city’s first fatality on Oct. 30. Essie May Johnson, 6, was the youngest to die.

“I went to findagrave.com and looked at Llano Cemetery and the people who died in October through December 1918,” Kuhlman said. “There were 70 deaths of people under 35. The same three months the year before there were 17. The year after there were 21.”

At the height of the pandemic, there were display ads in the Amarillo Daily News, one to buy a Hoover vacuum cleaner to clean up the Spanish flu, and the other for tricycles so children could get fresh air and avoid the Spanish flu.

“You can kind of see how private enterprise back then was wanting to make a little money off it,” Kuhlman said.

Do you know of a student, faculty member, project, an alumnus or any other story idea for “WT: The Heart and Soul of the Texas Panhandle?” If so, email Jon Mark Beilue at jbeilue@wtamu.edu.