|

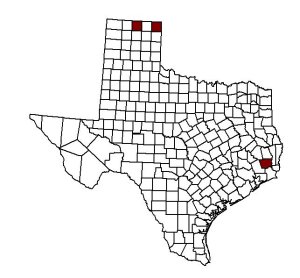

Map prepared by Greg T. Lewellen |

Microtus ochrogaster (Praire Vole)

Written by

Matt Poole (Mammalogy

Lab--Fall 2003)

Edited by Karah Gallagher and Jennifer Bailey

|

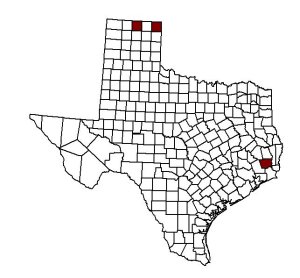

Map prepared by Greg T. Lewellen |

The prairie vole, Microtus ochrogaster probably originated from Asia and emigrated across the Bering Land Bridge into North America about 1.8 x 106 years ago (Zakrzewski 1985). Today the Prairie Vole occurs in Northeastern New Mexico (Finley et al. 1986), in the far northern Texas panhandle in Hansford and Lipscomb co., and in Hardin co. which is located deep into east Texas (Manning and Jones 1988), throughout the Great Plains of Oklahoma northward, then eastward to Ohio and then westward to the foothills of the Rocky Mountains (Findley 1954).

The prairie vole distribution can be influenced by the amount of evaporative water lost from their skin surface (such as their ears, nose, and appendages) (Getz 1965), distribution of vegetation, and amount of vegetative cover (Getz 1985).

Physical Characteristics:

Prairie voles are grayish-brown with some black and yellowish-brown on the tips of the longer hairs giving it a grizzled look (Mumford and Whitaker 1982), the sides are a paler color, the belly is a yellowish-orange color, and they have a short sharply bi-colored tail.

Hall (1981) did extensive studies on the external measurements of the prairie vole. Their total body length measures between 130-172mm. Their hindfoot measures 17-22mm. Their ear length measures 11-15mm. Their body mass weighs between 37-48g, though (Martin 1956) has recorded prairie voles up to a weight of 73g.

Armstong (1972) did extensive studies on the measurements of the cranium for both male and female Prairie Voles. The condylobasal length measures 29.5 and 29.3mm. The zygomatic breadth measures 16.6 and 16.7mm. The interorbital constriction measures 4.0 and 3.7mm. The prelambdoial breadth measures 9.8 and 9.6mm. The lambdoidal breadth measures 12.8 and 12.8mm. And they have a maxillary tooth row length of 7.2 and 6.9mm. Though they do not have a diastemal palate ridge (Carleton 1985), they do have a maticatory musculature associated with their cranium. And of the Microtus genus Microtus ochrogaster have the simplest teeth which are adapted for a herbivorous trophic niche, with a dental formula of i 1/1, c 0/0, p 0/0, m 3/3 total 18 (Carleton 1985).

The determining weight of becoming an adult is 45g (Calhoun 1946). Though Jameson (1950) believes that male prairie voles are sexually mature when the caudal epididmis is visible to the naked eye. And like some other male mammals male prairie voles have a baculum which consists of four parts (Carleton 1985). Females are considered sexually mature if either the corpora albicantia or the corpora lutea were present between the months of March and October, or if only the corpora lutea was present between November and February (Hamilton 1941). Also like many female mammals female prairie voles have nipples, 1-pectorial pair, and 2-inguinal pairs with a total of six (Carleton 1985).

Prairie voles have a unique digging style; digging involves the simultaneous use of their rear paws, in conjunction with the alternating use of the for-paws (Wolff 1985). Not only are prairie voles unique in their style of digging but they are also the best microtine swimmer, even though they avoid the water whenever possible (Evans et al. 1978).

When prairie voles are born they are un-pigmented, hairless, both eyes and ears are closed, their vibrissae are visible, their teeth have not erupted, and their anus is not visible (Nadeau 1985). Growth and development occurs most during the first 2-months (Hoffmeister and Getz 1968). The juveniles will go through two molts during their life time with the first occurring between 21-28 days old, and the second occurring between 40-84 days old (Richmond and Conway 1969a).

Another unique quality prairie voles contain is that they have the most efficient kidneys of any other microtine mammal and thus can consume higher molarities of salt water (Getz 1963).

Natural History:

Food Habits: Prairie voles feed on seeds, roots, green vegetation, dead vegetation, and insects whenever green vegetation is not available (Getz 1985). Calhoun (1946) reports, that in 1939, Hatfield reported that prairie voles have a high metabolism, and must eat at frequent intervals. Getz (1985) also found that prairie voles must contain forbs within their diet therefore graminoid vegetation alone may not be adequate (Cole and Batzli 1978). Prairie Voles main energy source comes from the food that they accumulate (Wunder 1985), and can sustain long periods with out water when they consume green vegetation (Getz 1963).

Reproduction: Prairie voles breeding season is divided up into a winter and a summer season (Gaines and Rose 1976), but there are considerable variations in their breeding seasons (Keller 1985), even though sexuality occurs throughout the year (Fitch 1957). There is usually a 2 month transition period where either sex may or may not be fecund depending on what population process have occurred (Keller and Krebs 1970). Krebs et al. (1969) found that in southern Indiana Prairie Voles had their highest breeding incident occurring in summer months.

Prairie voles become sexual mature when their body mass reaches a weight of 34g or heavier (Gaines and Rose 1976). Though Rose (1974) disagrees, and believes that sexual maturity is reached at 33g. Male prairie voles become sexually mature between 36-45 days old (Jameson 1948; Martin 1956; Fitch 1957).

Age and weight are not the only aspects that determine when a prairie vole becomes sexually mature or not. Population densities also can determine the age in which a prairie vole becomes sexually mature. In periods of peak population, sexual maturity is reached at a much lower body mass (Krebs et al. 1969).

Prairie voles display a monogamous mating system (Hoffman and Getz 1988) that will form pair bonds by preference for a familiar social partner (DeVries et al. 1996). Pair bonds will form, once two individuals mate with one another. Though unlike females, male prairie voles will not form a pair bond with a female if they have not had a sexual encounter within the first six hours upon meeting (DeVries et al. 1996). But once a male has mated he will continue to mount every 40-60 minutes for the rest of the next 24 hours (Insel et al. 1995). Once a male has mated his selective aggression and affiliation increases (Insel et al. 1995).

Female prairie voles first opportunity to mate will occur between the age of 33-34 days old. Of all the microtines, prairie voles have the shortest gestation period of 20 days (Fitch 1957), and will have their first litter at or around 60 days old (Richmond and Conway 1969b; Cole and Batzli 1978). The time it takes to have this litter will take approximately one hour from the first birth to the last birth (McGuire et al. 2003). This litter will be the smallest litter that they will produce and is not influenced by age or parity, though future litters will be influenced by age, conditions in mating colony, season, parity, and year (Gaines and Rose 1976). Females are considered pregnant by nipple size, the size of the pubic symphysis (Krebs et al 1969), or whenever the embryos become visible in the uterus which is usually on the sixth day after copulation (Hoffman 1958), though females rarely get a chance to reproduce for a second chance if they have reproduced during a summer peak season (Krebs et al. 1969).

Reproduction can be influenced by drought, seasons of low precipitation which have low reproduction rates (Martin 1956), and the best way to tell if a population is having a lot of breeding activity, is whether or not the percentage of females with medium to large nipples is high or low (Krebs et al

Behavior: Prairie voles are more nocturnal than diurnal. Many factors influence their activity such as the intensity of light, the temperature (how hot or cold it is), or even being in contact with the opposite sex can change their activity pattern. When the intensity of light is high and the temperature is high daily activity tends to increase (Calhoun 1946). Though prairie voles do have to be careful in summer heat, because the high temperatures leaves them susceptible to heat stress (Gaines and Rose 1976; Jameson 1948; Krebs et al. 1969; Martin 1956).

Prairie voles have been known to live in communal groups (Fitch 1957) which helps with the forming of pair bonds. If a pair bond is broken males will more readily form a new pair bond than will a female. Only about 13.8% of all females are susceptible to form a new pair bond (Pizzuto and Getz 1988). The only way a female will form a new pair bond is when they have prolonged direct physical contact with an individual (Curtis et al. 2003). Pair bonding is not decided upon the availability of males but it is pair-bonding behavior that decides whether or not they will form a new pair bond (Pizzuto and Getz 1988).

Juvenile prairie voles are very arrhythmic (Calhoun 1946) and more curious therefore more susceptible to trapping than any other species of Microtus (Krebs et al. 1969).

Habitat: Originally prairie voles inhabited prairie grasslands but due to the modification of the land for agriculture use, that habitat has been reduced (Getz 1985). Now they inhabit drier upland habitat (Findley 1954); grassy roadsides, along county roads, highways, railroads (Getz 1985); graminoid vegetation (Getz 1963); grass and weed communities (Krebs et al. 1969). In Illinois, prairie vole populations are highest in alfalfa fields, intermediate populations are found within bluegrass, and the lowest populations are found in tall-grass prairie. The alfalfa fields provide energy rich supply of food but little cover, though prairie voles prefer environments with dense cover which will protect them from avian predators (Getz 1985), this suggests that quality of food is more important than cover (Getz et al. 2001).

Economic Importance for Humans:

Prairie voles are a rodent that appears to be a valuable source for research. So therefore it serves as an important factor for humans.

Conservation Status:

The prairie vole is not endangered, rare, threatened in any way.

References:

Armstrong, D. M. 1972. Distribution of mammals in Colorado. Monograph of the Museum of Natural History, The University of Kansas, No. 3. University of Kansas Press, Lawrence.

Calhoun, J. B. 1946. Diel activity rhythms of the rodents, Microtus ochrogaster and Sigmodon hispidus. Ecology 26:251-273.

Carleton, M. D. 1985. Macroanatomy. Pp. 116-1175, in Biology of New World Microtus (R. H. Tamarin, ed.). Special Publication, The American Society of Mammalogist, 8:1-893.

Cole, F. R., and G. O. Batzli. 1978. The influence of supplemental feeding on vole population, Journal of Mammalogy 59:809-819.

Curtis J. T., R. J. Stowe, and Z. Wang. 2003. Differential effects of intraspecific interactions on the striatal dopamine in social and non-social prairie voles. Neuroscience 118:1165-1173.

DeVries A. C., M. B. DeVries, S. E. Taymans, and C. S. Carter. 1996. The effects of stress on social preferences are sexually dimorphic in prairie voles. Proc. National Academy of Science. USA 93:11980-11984.

Evans, R. I., E. M. Katz, N. L. Olsen, and D. A. Dewsbury. 1978. Comparative study of swimming behavior in eight species of muriod rodents. Bulletin Psychonomic Society 11:168-170.

Findley, J. S. 1954. Competition as a possible limiting factor in the distribution of Microtus. Ecology 35:418-420.

Finley, R. B. Jr., J. R. Choate, and D. F. Hoffmeister. 1986. Distribution and habitats of voles in southeastern Colorado and northeastern New Mexico. The Southwest Naturalist 31:263-266.

Fitch, H. S. 1957. Aspects of reproduction and development in the prairie vole (Microtus ochrogaster). Miscellaneous Publication of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas. 10:129-161.

Gaines, M. S., and R. K. Rose. 1976. Population dynamics of Microtus ochrogaster in eastern Kansas. Ecology 57:1145-1161.

Getz, L. L. 1963. A comparison of the water balance of the prairie and meadow voles. Journal of Mammalogy 44:202-207.

Getz, L. L. 1965. Humidities in vole runways. Ecology 46:548-551.

Getz, L. L. 1985. Habitats. Pp. 286-309. in Biology of New World Microtus (R. H. Tamarin, ed.). Special Publication, The American Society of Mammalogist, 8:1-893.

Getz, L. L., J. E. Hofman, B. McGuire, and D. W. Thomas III. 2001. Twenty-five years of population fluctuations of Microtus ochrogaster and M. Pennsylvanicus in three habitats in east-central Illinois. Journal of Mammalogy 82:22-34.

Hall, E. R. 1981. The mammals of North America. 2nd ed. John Wiley and Sons Publications, New York, 2:601-1181.

Hamilton, W. J., Jr. 1941. reproduction of the field mouse Microtus pennsylvanicus (Ord.). Cornell University. Agr. Exp. Sta. Mem. 237. 23p.

Hoffman, R. S. 1958. The role of reproduction and mortality in population fluctuations of voles (Microtus). Ecological Monographs 28:79-109.

Hofman J. E., and L. L. Getz. 1988. Multiple exposures to adult males and reproductive activation of virgin female Microtus ochrogaster

Hoffmeister, D. F., and L. L. Getz. 1968. Growth and age-slasses in the prairie vole, Microtus ochrogaster, Growth 32:57-69.

Insel T. R., S. Preston, and J. T. Winslow. 1995. Mating in the monogamous male; Behavioral Consequenses. Physiology & Behavior 57:615-627.

Jameson, E. W., Jr. 1948. Natural history of the prairie vole (mammalian genus Microtus). Miscellaneous Publication of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 1:125-151.

Jameson, E. W., Jr. 1950. Determining fecundity in male small mammals. Journal of Mammalogy 31:433-436.

Keller, B. L., and C. J. Krebs. 1970. Microtus population biology; III. Reproductive changes in fluctuating populations of M. ochrogaster and M. Pennsylvanicus in southern Indiana. Ecological Monographs 40:263-294.

Keller, B. L. 1985. Reproductive patterns. Pp. 725-778, in Biology of New World Microtus (R. H. Tamarin, ed.). Special Publication, The American Society of Mammalogist, 8:1-893.

Krebs, C. L., B. L. Keller, and R. H. Tamarin. 1969. Microtus population biology; demographic changes in fluctuating population biology: dispersal in fluctuating populations of M. townsedii Canadian Journal of Zoology 55:1825-1840.

Manning, R. W., and J. K. Jones, Jr. 1988. A specimen of the prairie vole, Microtus ochrogaster, from the northern Texas Panhandle. The Museum and Department of Biological Sciences, Texas Tech University, 40:463-464.

Martin, E. P. 1956. A population study of the prairie vole (Microtus ochrogaster) in northeastern Kansas 8:361-416.

McGuire, B. E., Henyey, E. McCue, W. E. Bernis. 2003. Parental behavior at parturition in prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster). Journal of Mammalogy 84:513-523.

Mumford, R. E., and J. O. Whitaker, Jr. 1982. Mammals of Indiana. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 537 Pp.

Nadeau, J. H. 1985. Ontogeny. Pp. 254-285, in Biology of New World Microtus (R. H. Tamarin, ed.). Special Publication, The American Society of Mammalogist, 8:1-893.

Pizzuto, T., and L. L. Getz. 1988. Female prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) fail to form a new pair after a loss. Behavior Processes 43:79-86.

Richmond, M., and C. H. Conway. 1969a. Management, breeding, and reproductionperformance of the vole, Microtus ochrogaster in a laboratory colony. Lab Animal Care 19:80-87.

Richmond, M., and C. H. Conway. 1969b. Induced ovulation and oestrus in Y. Journal of Mammalogy 62:213-215.

Rose, R. K. 1974. Reproductive, genetic, and behavioral changes in population of the prairie vole (Microtus ochrogaster) in eastern Kansas, Ph.D. Dissertation University of Kansas.

Wolff, J. O. 1985. Behavior. Pp. 304-372, in Biology of New World Microtus (R. H. Tamarin, ed.). Special Publication, The American Society of Mammalogist, 8:1-893.

Wunder, B. A. 1985. Energetics and thrmoregulation. Pp. 812-844. in Biology of New World Microtus (R. H. Tamarin, ed.). Special Publication, The American Society of Mammalogist 8:1-893.

Zakrzewski, R. J. 1985. The Fossil Record. Pp1-51, in Biology of New World Microtus (R. H. Tamarin, ed.). Special Publication, The American Society of Mammalogist 8:1-893.