|

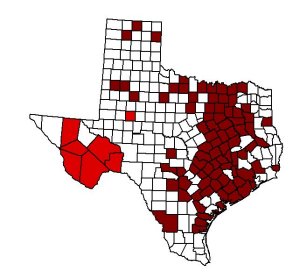

Map prepared by Greg T. Lewellen |

Spilogale putorius (Eastern Spotted Skunk)

Written by

Carlee Howard (Mammalogy

Lab--Fall 2003)

Edited by Karah Gallagher and Jennifer Bailey

|

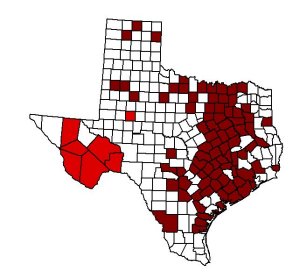

Map prepared by Greg T. Lewellen |

Spilogale putorius ranges from south-central Pennsylvania down the Appalachian chain to Florida, west to the Continental Divide, and south to Tamaulipas, Mexico (Kinlaw 1995; Van Gelder 1959). The eastern spotted skunk has been found in open lowlands, mountainous country, and at altitudes of 2,400 meters (Novak et al. 1987). By the 1940s, the eastern spotted skunk was reported in North Dakota, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, areas in which they had not previously occurred (Van Gelder 1959). The spread of the Spilogale putorius has been doubtlessly aided by man (Polder 1968). The movement of the eastern spotted skunk, in 1957, was due to farms that were being enlarged, fences removed or replaced, willows and large windbreak groves disappearing, and gullies being filled up causing the skunks to find a new habitat to live in (Polder 1968). Humans have also assisted the migration by draining the land and making it more suitable for habitation; by building houses and outbuildings which provide shelter for the skunk; by bringing in mice and rats as a source of food; by raising crops and storing them; and decreasing the number of predators (Van Gelder 1959). In Texas, the eastern spotted skunk occurs in the eastern one-half of the state east of the Balcones Escarpment, west into north-central Texas, into the panhandle, and south as far as Garza County (Davis and Schmildly 1994).

Physical Characteristics:

Spilogale putorius, eastern spotted skunk, has dense jet black pelage with white spots running down the back into four to six broken strips on its back (Howard and Marsh 1982). A white patch of hair is located on the forehead, behind both ears, and one on each side of the rump (Howell 1906). The patches of white behind the ears are usually continuous with the strips on the back (Davis and Schmildly 1994). The tip of the tail is tufted and white (Howell 1906). Spilogale putorius is the smallest of all the skunks and is more commonly associated with the weasel due to their elongated bodies (Kinlaw 1995). The pattern of their fur is helpful in making them invisible at night, even with moonlight while holding still (Kinlaw 1989). The ears are short and low on the side of their head (Davis and Schmildly 1994). They have five toes on each foot with long curved claws on the forefeet at the length of 7 millimeters. The claws are twice as long on their forefeet as on their hindfeet (Kinlaw 1995).

The external measurements of a male Spilogale putorius are approximately: total length - 512 millimeters, length of tail - 204 millimeters, and the hindfoot - 47.5 millimeters. The measurements of a female include: total length - 482 millimeters, length of tail -189 millimeters, and hindfoot - 42 millimeters. A male’s average size weight is 700 grams compared to a female of 450 grams (Howell 1906).

The dental formula for Spilogale putorius consists of incisors 3/3, canines 1/1, premolars 3/3, and molars 1/2, and a total of 34 teeth (Kinlaw, 1995, Davis and Schmildly 1994).

Natural History:

Food Habits: Spilogale putorius is very predatory, opportunistic, (Kinlaw 1989) and omnivorous feeders (Crabb 1941). Their long weasel shaped bodies allow them to pursue their prey into burrows (Kinlaw 1989). Food selection of the eastern spotted skunk is seasonal. They will eat whatever is available, but would prefer small rodent for their prey (Kinlaw 1989; Selko 1937). During the winter, the food is usually of the mammal origin consisting of cottontail rabbit and corn. During the spring, food consists of mostly mammals such as the native field mice and insects. Insects are the primary choice during the summers along with plants, birds, and bird’s eggs. In the fall predominantly insects are eaten with fruits, some mice and a few birds (Crabb 1941). Spilogale putorius kill their prey by rapid vicious bites to the head and the neck (Manaro 1961). If an eastern spotted skunk develops a taste of poultry, it can be damaging to the agriculturist. Spilogale putorius are excellent rat-catchers and get rid of barn pests, which is actually an asset to the agriculturist (Davis and Schmildly 1994).

The eastern spotted skunk has an interesting technique to opening eggs. Spilogale putorius will first try to break the egg by biting it. Eventually they will give up on biting, and will propel the egg underneath its body and give a quick kick backwards, which is repeated until the egg is broken (Van Geldler 1953).

Reproduction: Mating is aggressive between the male and female which includes hissing and high pitched chattering vocalizations (Teska et al. 1981). The eastern spotted skunk vocalizes only by grunts, barks, and high-pitched screeches (Manaro 1961). Males will travel long distances during the months of March and April to mate with a female (Mead 1968) who give birth in May and June (Kinlaw 1989). The gestation period lasts 50-65 days with no known delayed implementation (Davis and Schmildly 1994; Mead 1968). Spilogale putorius are able to mate twice a year, with a second litter born in August, although this may not occur in all females (Mead 1968). The litter size may range from one to six with an average size being four (Novak 1987). A study was done in an Iowa agricultural habitat, which showed a sex ratio of 1.68 males to 1 female. The eastern spotted skunk can develop a dense population in a suitable habitat and the sex ratio is biased towards males (Kinlaw 1989).

The young are born blind and helpless weighing nine grams each (Howard and Marsh 1982; Crabb 1944). The fur of the young is very fine with distinct white and black markings (Kinlaw 1995). Young Spilogale putorius open their eyes at 30-32 days and begin to walk and play at 36 days (Davis and Schmildly 1994; Crabb 1944). At 46 days of age the eastern spotted skunk is able to emit a musk, therefore are weaned at 54 days (Howard and Marsh 1982). The young will reach adult size at three months, while reaching maturity at nine to ten months of age (Davis and Schmildly 1994). The male Spilogale putorius do not assist in the care of the young during any time of the pregnancy or thereafter (Kinlaw 1995).

Behavior: Spilogale putorius are nocturnal and are rarely encountered at night with the moonlight (McCullough and Fritzell 1984). The two peaks of activity are shortly after sunset (Larsen 1968) and the other just prior to sunrise (Manaro 1961). However during the spring and summer, the Spilogale putorius are active for longer periods of time than during the winter and fall (McCullough and Fritzell 1984). Spilogale putorius are more agile and alert than striped skunks, and they are good climbers (Kinlaw 1989; Cuyler 1924). Overall the eastern spotted skunk is secretive in its habits, but will venture out when curiosity overcomes them (Manaro 1961). The home-range size and movements during the spring are due to the breeding season or an indication that the population has a low density. The largest home-range is during the spring (McCullough and Fritzell 1984). Eastern spotted skunks do not hibernate; however, they may go into periods of low activity or winter sleep during bad weather to help conserve their body fat (Howard and Marsh 1982; Kinlaw 1995).

Spilogale putorius will sleep with their head and forelegs tucked beneath their abdomen, the crown of the head, shoulders, hind feet, and tail are in contact with the ground (Manaro 1961).

The discharge of a musk by the Spilogale putorius is not a spray, but rather two or three drops of fluid expelled (Manaro 1961). This is a threat behavior. The eastern spotted skunk will run at their opponent, then stop abruptly and elevate their hind legs balancing on the forelegs which is commonly known as the “hand-stand” (Johnson 1921; Howell 1919). The skunk will turn its tail to the side allowing the anal gland to be pointed at their enemy (Kinlaw 1995). As the distance decreases between the objects, the skunk may clap its hands and hiss at the challenger (Johnson 1921). Once the skunk is within two meters of the intruder they will drop to all fours in a horseshoe shape allowing their anal end and their head to face the intruder (Kinlaw 1995), often emitting a musk from this position (Manaro 1961). If the Spilogale putorius is dying, it will release all of its supply of musk before its heart stops (Cuyler 1924).

People are affected by the liquid which causes the eyes to burn and tears to flow rather freely for several minutes (Cuyler 1924). Eliminating the odor to the skin may take several washing because a person cannot deodorize the skin (Cuyler 1924). Removing the smell from your clothes can be done by adding ammonia to the wash, but still it will need more than one wash (Howard and Marsh 1982). When a dog or a cat comes in contact with a skunk usually tomato juice will help remove the smell with a bath (Howard and Marsh 1982).

Habitat: Requirements for a den site selection include darkness and protection from weather and natural enemies (Kinlaw 1995). Spilogale putorius thrive in a variety of brushy, rocky, and wooded habitats (Kinlaw 1989), preferring rocky canyons and outcrops if available (Davis and Schmildly 1994). Eastern spotted skunks may live in plains of short grass but unfortunately this does not provide much protection from predators (Manaro 1961). The den sites may vary depending on the surrounding environment. In a mountainous region, a crack or a crevice in the rocks would offer protection from predation for the eastern spotted skunk (Kinlaw 1989). Spilogale putorius may live in or around farmlands, and will often den under buildings, haystacks, woodpiles, straw piles, corncribs, grain elevators, or wells with rock walls (Kinlaw 1995). Their ability to climb allows them to live in a hollow tree or in an attic of a building (Davis and Schmildly 1994). Eastern spotted skunks may move from den to den and more than one skunk has been captured at the same den site in capture-recapture studies (Manaro 1961). Spilogale putorius may move dens due to a disturbance by dogs and humans around their territory (Kinlaw 1995). The eastern spotted skunk does not have a permanent den or are more commonly known as being nomadic which means they do not defend a home range or occupy a territory (Howard and Marsh 1982).

Economic Importance for Humans:

The pelt of the eastern spotted skunk was an insignificant fraction of the modern fur trade (Kinlaw 1995). During 1975-1976, the United States total number of pelts for the spotted skunks was 6,834. The average price of a pelt was $2.00 a piece making the total value be $13,668 (Howard and Marsh 1982). Spilogale putorius pelts reached the price of $3.41 in 1982-83 in Canada and the United States. This made the skunk the 16th most important furbearer in terms of total harvest value with a total amount of $950,000 (Novak et al. 1987). Management involves two opposing approaches depending on the region and situation: 1) to increase skunk population density as desirable for bearers or 2) or to decrease their numbers when they become pests (Howard and Marsh 1982; Kinlaw 1995).

Conservation Status:

The eastern spotted skunk has had a rapid decline in numbers throughout most of the Midwest, which used to be their most abundant territory. New larger farms have destroyed fence row, creek bottoms, and small wood lots, and torn down old farm buildings to make a new space for their “cleaner” farmland. This has probably played a small role in the decline of the species (Kaplan and Mead 1991; Choate et al. 1973).

Spilogale putorius are endangered in Missouri and threatened in Kansas and Iowa (Mead 1968). In Montana, the eastern spotted skunk is listed as a “species of special concern” and in Nebraska a “species of need of conservation.” The Spilogale putorius are rare in the states of North Dakota and Oklahoma. In Texas, Arkansas, Mississippi, South Dakota, and Louisiana the status of the Spilogale putorius has not been documented (Kaplan and Mead 1991).

Mortality of the eastern spotted skunk is mainly by automobile road kills (Novak et al. 1987; Howard and Marsh 1982). Some predator control tactics of the Spilogale putorius are being trapped, shot, or poisoned. Predators of the eastern spotted skunk include the great horned owl, bobcat, domestic dogs (Novak et al. 1987), coyotes, and foxes (Davis and Schmildly 1994; Howard and Marsh 1982). In recent years the Eastern spotted skunk appears to be a reservoir of disease (Hendricks 1965). Spilogale putorius can carry fleas, lice, mites, ticks, and a variety of other endoparasites, but mortality of this is undetermined (Howard and Marsh 1982; Novak et al. 1987). Rabies is the most serious threat that skunks provide to humans (Howard and Marsh 1982; Hendricks 1969). In Texas, less than one percent of skunk rabies cases have been reported since 1978 (Kinlaw 1995). However, Spilogale putorius are commonly known to contract microfilaria, listeriosis, mastitis, tularemia, distemper, and Q fever (Kinlaw 1995).

References:

Choate, J. R., E. d. Fleharty, and r. J. Little. 1973. Status of the spotted skunk Spilogale putorius in Kansas, United States of America. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science 76:226-233.

Crabb, Wilfred D. 1941. Food habits of the prairies spotted skunk in Southeast Iowa. Journal of Mammalogy 22:349-364.

Crabb, Wilfred D. 1944. Growth, development and seasonal weights of spotted skunks. Journal of Mammalogy 25:213-221.

Cuyler, W. Kenneth. 1924. Observations on the habits of the striped skunk (Mephitis Mesomelas Varians). Journal of Mammalogy 5:186-189.

Davis, William B. and David J. Schmildly. 1994. The Mammals of Texas. University of Texas Press, Austin.

Hendricks, S. L. 1965. Rabies in wild animals trapped for pelts. Bulletin of the Wildlife disease Association 5:231-234.

Howard, Walter E. and Rex E. Marsh. 1982. Spotted and hog-nosed skunks. Wild Mammals of North America. Baltimore, Maryland: The John Hopkins University Press.

Howell, Arthur H. 1919. The Florida spotted skunk as an acrobat. Journal of Mammalogy 1:88.

Howell, Arthur H.1906. Revision of the skunks of the genus Spilogale. North American Fauna 26:1-55.

Johnson, Charles E. 1921. The “Hand-stand” habit of the spotted skunk. Journal of Mammalogy 2:87-89.

Kaplan, J. b. and R. A. Mead. 1991. Conservation status of the Eastern spotted skunk. Mustelid & Viverrid Conservation Newsletter 4:15.

Kinlaw, Al. 1989. Estimation of spotted skunk (Spilogale putorius) population with Jolley-Saber model and an examination of violations of model assumptions. M. S. thesis, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, 202 pp.

Kinlaw, Al. 1995. Spilogale putorius. Mammalian Species 511: 1-7.

Manaro, A. J. 1961. Observations on behavior of the spotted skunk in Florida. Quarterly Journal of the Florida Academy 24:59-63.

McCullough, C. R. and E. K. Fritzell. 1984. Ecological observations of Eastern spotted skunks on the Ozark Plateau. Transactions of the Missouri Academy of Science 18:25-32.

Mead, R. A. 1968. Reproduction of eastern forms of the spotted skunk (genus Spilogale). Journal of Mammalogy 156:119-136.

Novak, M., J. A. Baker, M. E. Obbard, and B. Mallock. 1987. Striped, spotted, hooded, and hog-nosed skunk. Wild Furbearer Management and conservation in North America. Toronto, Ontario Trappers Association 599-613.

Polder, E. 1968. Spotted skunk and weasel populations den and cover usage in Northeast Iowa. The proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science 75:142-146.

Selko. L. F. 1937. Food habits of Iowa skunks in the fall of 1936. The Journal of Wildlife Management 1:70-76.

Teska, W. R., E. N. Rybak, and R. H. Baker. 1981. Reproduction and development of the pygmy spotted skunk. The American Midland Naturalist 105:390-392.

Van Gelder, Richard. 1959. A Taxonomic Revision of the Spotted Skunks (Genus Spilogale). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History Volume 117, Article 5.

Van Gelder, Richard. 1953. The egg-opening technique of a spotted skunk. Journal of Mammalogy 34:255-256.